Sloth Facts | Peruvian Amazon Wildlife Guide

The leisurely sloth moves through the trees at a lethargic pace. This arboreal animal pays little heed to cleanliness. Its matted hair hosts communities of parasitic moths, mites, and green algae that help them remain camouflaged from jaguars and eagles.

There are two families of sloth found in the tropical rain forests of Central and South America: the herbivorous three-toed sloth and the omnivorous two-toed sloth. Three-toed sloths are more active during the day, so you have a better chance of sighting one than the predominantly nocturnal two-toed sloth. There are six extant species, the most common being the brown-throated sloth, in addition to the pale-throated sloth, Hoffman’s two-toed sloth, Linnaeus’s toe-toed sloth, the maned sloth (classified as vulnerable), and the critically endangered pygmy three-toed sloth.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Has a round head and flattened face with tiny ears, beady eyes, and a snub nose.

The two-toed sloth is slightly bigger than the three-toed.

Well-developed arms are long and boney, each with two or three curving claws that hook over and grasp the branches.

Fur harbors algae and mold, giving it a green tinge.

Spends most of its time suspended upside down, using its claws to grasp branches.

Claws are curved and measure 3 to 4 inches long.

Two-toed sloths measure up to 27 inches long and weigh up to 19 pounds.

HABITAT AND RANGE

The sloth is found in Central and South America, hanging from the tall trees in cloud and rain forests. You may see an inert sloth tucked onto a tree branch, basking in the sun. The thick, matted coat of sloths helps keep them insulated, but dropping nighttime temperatures lower their body temperature, and, like reptiles, they rely upon the sun to elevate their temperature back to normal. If the sloth’s body temperature drops too low, the bacteria in the gut (which aid in digesting its leafy diet) will stop working, and the sloth may starve. Eagles prey upon relatively defenseless sloths resting in the cecropia crowns, plucking them from the open canopy.

BEHAVIOR AND COMMUNICATION

The languid sloth, in a state of relative torpor, lounges in its treetop home. The sloth spends between 15 and 18 hours curled up asleep each day. At their fastest speed, sloths travel less than 1 mile in four hours through the trees. While on the forest floor, they move at an even more lackluster pace, struggling to crawl or simply falling over.

Their digestive system works just as slowly. The low metabolism of a sloth is half the rate of other similarly sized animals, and food may linger in the stomach for up to one week. Therefore, sloths have developed extremely large intestinal tracts, a four-chambered stomach, and bacteria in the stomach that helps process ample amounts of tough leaves. This low-energy diet results in the slow movement and long sleeping periods of the sloth.

In line with its slow lifestyle, the sloth defecates only about once a week. At this time, it descends to the forest floor, where it excavates a small hole with its hind claws. It then excretes its dung, covers the hole with leaves, and returns to its arboreal habitat. Sloth moths, which live in the fur of the sloth, lay their eggs in the feces where they hatch and feed, continuing the cycle of reproduction.

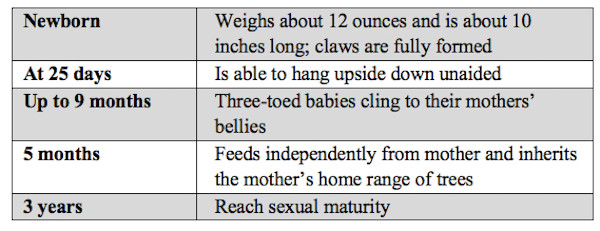

SLOTH DEVELOPMENT

FEEDING HABITS

High in the trees, a sloth may be found feeding on one of its favorite foods: cecropia leaves. The sloth’s diet is made of tough foliage, which is difficult to digest. They have a four-part stomach that slowly breaks down these leaves with bacteria. In fact, it can take up to one month for a sloth to digest one meal. Their tongues are thick and densely covered with sharp, backward-directed spines that help saw apart thick leaves.

BREEDING AND REPRODUCTION

Sloths mate and give birth to their young in trees. Gestation lasts approximately six months, and the female produces one offspring each year—meaning half of her adult life is spent pregnant. Females give basic care to their young but are not the most devoted parents; if her baby falls from a tree, a mother may ignore its cries for help, unwilling to leave the safety of its leafy bower. At five months, the young sloth is left to fend for itself, living in the trees of its mother’s previous home range. Juveniles become sexually mature at 3 years old. Sloths may live up to 20 years or longer.

CONSERVATION

Harpy eagles, anacondas, jaguars, ocelots and humans prey upon sloths. Poachers take sloths for their meat or to sell in the illegal pet trade. In addition, sloths risk electrocution from poorly insulated power lines. Deforestation caused by ranching, agriculture, urban expansion and logging threatens their habitat. When forests are fragmented, sloths are unable to move between the trees that shelter them from predators, and they must resort to crawling exposed on the forest floor. They also lose essential food sources, and breeding become challenging. Conservation organizations such as World Wildlife Fund are helping protect the tracts of tropical rain forest these sloths call home.