A PERSONAL REFLECTION ON THE U.S. IVORY CRUSH

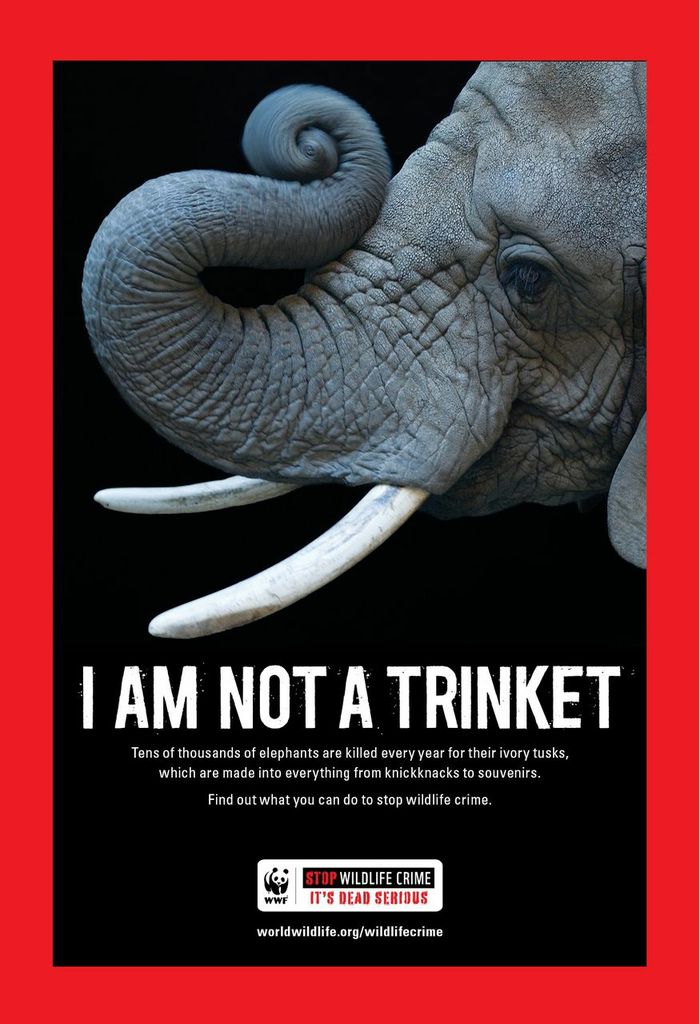

Banner symbolizing the 35,000 elephants killed by poachers last year. U.S. ivory crush, Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, Colorado

Two years ago when I was on safari in Botswana, I saw my first herd of wild elephants. We heard them first—a low, rumbling thunder in the distance. Then, out of the forest they emerged, the great gray pack crashing through a pool of standing water, so close they sent spray into our open-sided safari truck. The herd, at least 50 strong, trundled on through the wooded marsh, and we grinned as we watched a youngster struggle to keep up, running at full clip and trumpeting shrilly as if to say, “Wait for me! Wait for me!”

Later we would spend a half-hour watching a lone male bull eating—tearing branches off the mopane trees with his enormous trunk, curling it to hold them, stripping leaves and chomping noisily, just feet away.

I had never seen such a magnificent beast. He was enormous. His skin was deeply furrowed and crazed with creases. His tusks were grand. If there was ever an emblem of the African wild, this massive elephant was it. Yet I was equally enchanted by the week-old infant we later saw along the banks of the Chobe River, so tiny it could take shelter in the shade beneath its mother’s belly.

Being in the presence of wild elephants held a special magic for me. And so it was with anguish that I watched the ivory remains of some 2,000 elephants destroyed by the U.S. government last week, an event I was privileged to witness alongside senior government officials and representatives from WWF and other conservation organizations.

WITNESSING THE DESTRUCTION OF THE U.S. IVORY STOCKPILE

The crush consigned some six tons of confiscated illegal ivory – the full U.S. stockpile – to a massive rock crusher erected at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge outside Denver. The event, designed for symbolic impact, was meant as an unequivocal statement to the world that the United States will not support ivory trafficking in any form.

The pile of ivory before us, as we stood on the plains beneath a sky too bright and too blue for such a somber event, was sobering. There were giant tusks weathered brown with age, white tusks polished smooth, tusks carved with intricate scenes and images. On an adjacent table were ivory figurines – many were Buddhas, crafted for the largely Asian buyers’ market. And nearby was a rectangular glass bin filled five feet high with ivory jewelry and trinkets: bracelets, earrings, talismans – a full ton contained herein alone.

Ivory figurines to be destroyed at U.S. ivory crush, Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, Denver. Colo. Nov. 14, 2013. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

The first tusks were placed, silently, reverently, into the steel bucket of a front-end loader by representatives of the conservation groups on hand. At the direction of Daniel Ashe, head of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the loader hoisted them into the crusher’s mouth. A crowd of 200 or so looked on, including many journalists from news organizations around the world.

As officials continued to transfer the ivory to the loader, bucket after bucket was placed into the crusher and pulverized. I stood watching the cloud of ivory dust obscuring the clear lines of the Rocky Mountains in the distance, thinking about the elephants I was awed by in in Africa.

One of many loads of ivory to be delivered to the crusher – six tons in all were pulverized. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

Though the crush was not a burning, the dust gave the effect of smoke, and I had a sense we were witnessing a funeral pyre. A funeral for elephants, whose intelligence, deep emotions, and huge, wondrous bulk are being sacrificed at a rate of nearly one hundred per day to feed a growing demand for ivory status symbols. For small carvings. For souvenirs.

As I looked on, I ached for the human condition, and our capacity for moral depravity.

At one point or another, many of us who were present succumbed to tears. For some, it was during the crush itself, as the dust from dead elephants’ tusks rose in a cloud against the brilliant sun. For others, it was in listening to gruesome statistics about the rate at which elephants are being slaughtered, or hearing from government officials whose fierce desire to crack the poaching cartels is inhibited by ever more squeezed federal budgets.

For me, it was in trying to fathom how anyone could summon the will to shoot or poison these social, nurturing animals to feed a market of ignorant and vain consumers. How, especially, poachers could kill elephants, then lurk in wait to kill more of them when the survivors returned to the scene where their family members had been felled. The irony of this – that poachers would take advantage of grieving elephants, ‘easy pickings,’ was more than I could bear to think about.

How could anyone not want their child – their grandchildren – to have the opportunity, or at least the possibility, of seeing an elephant in the wild? Yet at the rate poaching has escalated today, with 35,000 elephants killed in the past year alone, Africa’s elephants could be gone in a decade.

One ton of ivory jewelry and trinkets was among the U.S. stockpile of confiscated illegal ivory destroyed. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

I know, too, that elephant ivory represents ready cash for legions of impoverished Africans, and those people who kill elephants to get money for their families’ needs see but a fraction of the profits that go to the cartels that now run the world’s $10 billion illegal ivory trade.

And yet I came away from the ivory crush with renewed hope that Africa’s elephants can be saved.

AMIDST THE DUST OF TUSKS, HOPE RISES

Like some, I wondered about the effectiveness of an event like the U.S. ivory crush, or Kenya’s public burning of five tons of ivory in 2011. Critics say such actions meant to “send a message to poachers” won’t do a thing to halt the poaching. But what I witnessed at this event was more than just a statement to poachers. It was something bigger. Symbolic, yes. But through symbols, we derive meaning and truth.

As David Hayes, former deputy secretary and chief operating officer for the U.S. Department of the Interior, told journalists covering the crush, “Destroying the U.S. stock of ivory is an acknowledgement of what ivory really is: a death warrant for the elephants.” By smashing ivory artifacts that would be worth millions on the black market, public awareness of the issue is heightened and a new direction is being blazed for responding to the crisis.

At a media symposium held beforehand, a panel of high-level government officials and conservation leaders spoke of concerted, collaborative efforts that would meet the illicit ivory trade head-on. As the crisis has escalated, so must the response, in a manner as unprecedented as the poaching epidemic itself. The ivory trade is now commandeered by sophisticated criminal syndicates, many with ties to terrorist organizations, said Crawford Allan, director of TRAFFIC North America, the wildlife trade monitoring organization jointly sponsored by WWF and IUCN.

“Our game has to match their game,” said Ashe.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Director Daniel Ashe addresses guests at the federal government’s ivory crush in Denver Nov. 14. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

Ashe praised President Obama’s executive order on wildlife trafficking last July, which paved the way for an “all-of-government” response that would require an “all-of-globe” partnership to carry out. A multi-pronged approach is essential, Ashe said. In the U.S., it brings together the resources of the departments of Justice, State and Interior in a synergistic move never before undertaken. The executive order requires the U.S. government to have a strategy in place by January 2014, including how to address the existing legal trade in ivory that’s still permitted in the U.S. (ivory acquired prior to the 1989 ban), which often provides a smokescreen for contraband ivory.

Many in the audience, myself included, were surprised to learn that the U.S. is the world’s second largest market for ivory after China, though the Asian market – including Thailand and Vietnam – is by far the biggest. Officials agreed that globally, greater efforts will be required in the sectors of law enforcement, diplomacy and policy, and education, the latter charged with crafting culturally sensitive strategies to address demand.

Contraband ivory figurines seized by U.S. government and crushed on Nov. 14, 2o13. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

Peter Knights, an economist who is executive director of WildAid, said, “We’ll never solve this problem until we tackle demand…I don’t think we can’t enforce our way out of this problem.” But he believes that “China as a major market has a huge capacity for change.”

Grace Ge Gabriel, Asia regional director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, agrees. She thinks part of the answer may lie in encouraging contemporary China to re-embrace to its Taoist heritage, an ancient philosophy in which heaven, earth and people existed in perfect harmony.

“The solution lies in restoring the moral essence of Chinese culture back into society – to built it back into ordinary Chinese citizens,” as well as into government policy.

Seventy percent of Chinese do not realize that ivory comes from dead elephants, said Gabriel. Most think tusks fall out like teeth, and the elephant grows new ones. Yet surveys show that when they learn the truth, the population most likely to buy ivory indicates that the likelihood of their doing so falls from 54% to 26%.

Dr. Paula Kahumbu, Kenyan conservation leader, flanked by actresses Joely Fisher (right), Kristin Davis (left), and David Hayes on the far left. Photo: Wendy Worrall Redal

In Africa as well, cultural values must shift back to an age in which humans lived harmoniously with the continent’s iconic wildlife, said Paula Kahumbu, executive director of WildlifeDirect, a Kenyan-based conservation organization that leads the HANDS OFF OUR ELEPHANTS campaign with Margaret Kenyatta, First Lady of Kenya, to mobilize African leaders to protect elephants.

Second only to Tanzania in illegal ivory trafficking, Kenya’s rampant elephant massacre reflects a condition in which modern-day Africans have lost touch with an elemental sense of who they are, said Kahumbu.

Second only to Tanzania in illegal ivory trafficking, Kenya’s rampant elephant massacre reflects a condition in which modern-day Africans have lost touch with an elemental sense of who they are, said Kahumbu.

“Africans revere animals like elephants. They are part of our identity. That sense is being lost as Africans modernize.” It’s essential to restore pride among Africans in their heritage, she said. While demand for ivory outside of Africa drives the problem, “the front line is our communities who live with these magnificent animals.”

Helping those communities recognize the economic value of keeping elephants and other wildlife alive is crucial, says Kahumbu, who noted that 12 percent of Kenya’s economy is based on tourism, most of the that from the safari sector.

Despite the gravity of the situation, Kahumbu finds hope in the message sent by the crush.

“It’s heartening. People on the other side of the planet are coming together to protect a species that only exists in Africa.”

THE POWER OF STORYTELLING – AND RETELLING

The more the elephant’s story can be told, the greater the global response will be. Yet it’s crucial to share more than just statistics, Kahumbu said. Hearts are moved – and action is taken – when people understand the real nature of elephants.

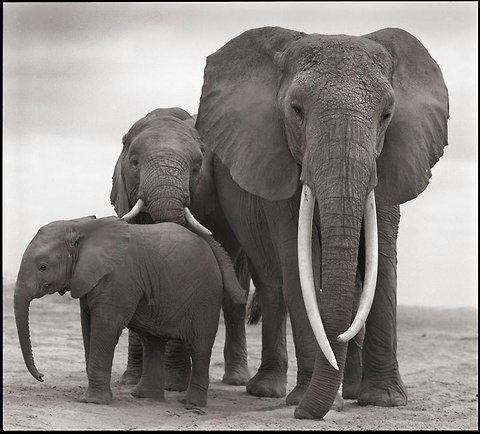

In Kenya’s Amboseli National Park, she said, “Every individual elephant is known as a person. It has a family, children, grandchildren.” When she took Kenya’s First Lady Margaret Kenyatta to meet the elephants of Amboseli, a Maasai woman who lived with the elephants for 17 years told her stories about them. The most powerful was the story of Qumquat, one of the park’s best-known females, an elderly matriarch of a family of 29.

Amboseli matriarch Qumquat with her offspring. The elephants were shot and killed by poachers in 2012. Photo: Nick Brandt, republished from Dot Earth blog.

Qumquat and her two daughters were gunned down by poachers last year, along with most of the members of their family. Their faces were hacked off, to ensure that every bit of their ivory was salvaged – about a third of the tusks lie buried within the skin.

When rangers found the carnage, Qumquat’s 10-month-old calf was standing over his mother’s carcass. Traumatized at having witnessed his mother shot and butchered, the calf stood vigil all night, alone. It was rescued and transported to the elephant orphanage at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Nairobi, where far too many of its young peers are also ending up, sometimes only to be returned to the wild and slaughtered for their own ivory after a few years’ time.

“The soul of the human species is at stake if we allow them to go extinct,” said actress Kristin Bauer, speaking to guests at the crush in Denver.

But clearly, at last week’s event, an awakening in human hearts was palpable. And a commitment to real solutions was on everyone’s agenda.

“There’s something magical, mystical, religious, about elephants,” said Robert Dreher, acting assistant attorney general for the U.S. Justice Department. “And we are responding.”

“But perhaps the most important lesson I learned is that there are no walls between humans and the elephants except those that we put up ourselves, and that until we allow not only elephants, but all living creatures their place in the sun, we can never be whole ourselves.”

— Lawrence Anthony, The Elephant Whisperer

Learn more about how WWF’s African Elephant Program is helping to combat poaching and protect these endangered animals. And join Natural Habitat Adventures on an African safari to see elephants in the wild — responsible ecotourism sends an important message to African communities that wildlife is worth more alive than dead.