Surprisingly, the most influential factor in determining where mammals can thrive isn’t human activity but climate.

When people are deciding where to live, factors such as a community’s cost of living, employment opportunities, ease of transportation, and proximity to family and friends are usually considered on a somewhat equal basis. It turns out that for other mammals, the process is a bit more straightforward. While you might think that lack of human activity would be the top determining factor for where wild animals choose to live, it isn’t. Climate, however, is.

And once different wildlife species do decide where to live, who resides alongside them matters. Cooperative hunting, using the same signals to communicate the same information and resource sharing are all examples of “co-culture” relationships that have been observed between distinct animal species—and they matter in substantial ways.

However, to fully understand other animals’ social functioning and structures, some animal behaviorists argue that we need to pay more attention to the “social side” of sleep.

Using data from more than 6,000 camera traps across the United States, researchers recently mapped the locations of populations of 25 mammal species.

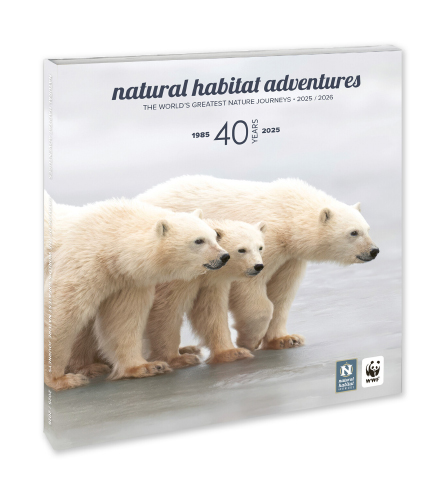

Choosing where to live: climate counts

While human activity has had a massive effect on the natural world, a new study—one of the largest camera-trap data analyses ever done—finds that climate is the most influential factor in determining where mammals can succeed.

Researchers from North Carolina State University said the goal of their study, the results of which were published in the science journal Diversity and Distributions in June 2024, was to compare the importance of climate versus human factors in where mammals choose to live. To do so, the scientists collected data on 25 mammal species from 6,645 locations across the United States. The data came largely from Snapshot USA, which is a national, mammal, camera-trap survey conducted with collaborators across the country.

It’s typically thought that humans have changed our landscapes so much that we have become the primary determinants of where wild animals can live. But the North Carolina State University researchers found that climate, including temperature and the amount of rainfall, was, in fact, the most important element across most of the species they observed.

Snowshoe hares are mainly nocturnal, and they don’t hibernate. They are shy and secretive, and they spend most of the day in shallow depressions scraped out under clumps of brush, ferns or piles of timber. The animals don’t fare well around agriculture or people.

Significantly, though, human activity in the form of agriculture and large population centers was still consequential. Some species struggled in the presence of farms and cities, but many thrived. For example, the Eastern gray squirrel does well when humans are around, but the Eastern fox squirrel prospers around agriculture but not as well around people. The snowshoe hare does poorly around both agriculture and people. Those differences are seen in many other species.

This information helped the researchers create maps which predict how common various mammals are across the contiguous U.S., which allowed them to separate the country into regions based on what kinds of mammals were found in each. These regions, known as ecoregions, are commonly used when studying plants but had never been applied to mammal populations.

By constructing mammal-species ecoregions and then comparing them to plant ecoregions, the researchers found striking similarities between the two. For instance, in the Eastern deciduous forest ecoregion where there is a lot of rainfall, more plants grow. That lines up with a greater abundance of mammals in that region because more plants mean more food for those animals to eat.

In contrast, the Eastern fox squirrel does well around agriculture but not around people. The squirrels prefer open, savanna-like habitats, where trees are spaced far apart and the understory is open. In agricultural areas, they eat corn, fruit, oats, soybeans and wheat.

This work sheds light on how climate change will affect wildlife populations. By identifying climate as the number one influence on a mammal’s habitat choice, scientists have a new tool for predicting the impacts of climate change on various mammal groups. Rising global temperatures will influence precipitation levels and plant growth and cause shifts in where animals choose to live. Understanding these factors will help make sustainable decisions about mammal population management in the future.

Residing side by side: co-cultures climb

Co-cultures—such as communicating by signals, cooperative hunting and resource sharing—are mutual relationships between animal species that go beyond one species watching and mimicking another’s behaviors. In co-cultures, both species influence each other in substantial ways, say researchers from France’s Academic University, Hubert Curien Multidisciplinary Institute and the University of Strasbourg and Japan’s Kyoto University and Nagasaki University, who published their results in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution in September 2024.

Co-culture challenges the notion of species-specific culture, underscoring the complexity and interconnectedness of human and nonhuman-animal societies, and between nonhuman-animal societies. These cross-species interactions result in behavioral adaptations and preferences that are not just incidental but represent a form of convergent evolution.

Ravens and wolves have a special co-culture relationship. Like many scavengers, ravens are tied to large predators that serve as potential food providers; in this case, carrion. Because of their close association with wolves, ravens don’t arrive soon after a kill but are there when a wolf kill is made. Too, ravens make lots of noise when they find a dead animal, drawing attention to the carcass so that larger scavengers can open the hide for them. Ravens have also been known to grab sticks and play tug-of-war with wolf puppies, to fly over young wolves with sticks and tease the small canines into jumping up to grab them, and even to boldly pull the tails of wolves to initiate a reaction. Some scientists have theorized that individual ravens may even develop special bonds with individual wolves within a pack.

In Tanzania and Mozambique, for example, a co-culture exists between humans and honeyguides, where the birds lead humans to honeybee nests. Co-cultures also encompass cooperative scavenging between ravens and wolves, cooperative hunting between false killer whales and bottlenose dolphins, and signal sharing between distinct species of tamarins.

Ultimately, this interspecies sharing of culture could drive evolution, say the French and Japanese researchers. Cultural behaviors that enhance survival or reproductive success in a particular setting can lead to changes in population habits that, over time, could drive genetic selection.

To extend our understanding of co-cultures, the researchers state that future studies could start by investigating wild animals in urban environments. Urban animals modify their behaviors, learning and problem-solving skills to cope with city challenges, reflecting a dynamic response to urban landscapes. Similarly, humans alter their urban spaces, influencing wildlife behavior and evolution. This reciprocal adaptation between humans and wildlife is fundamental to understanding co-cultures.

Urban animals, such as coyotes, modify their behaviors to cope with city challenges. Similarly, humans alter their city spaces, influencing wildlife behavior and evolution. This reciprocal adaptation between humans and wildlife is fundamental to understanding co-cultures.

Future research is also needed to examine the possibility of cultural and genetic co-evolution: the idea that species’ cultures and genomes are evolving in concert. A key question is, in the context of co-culture, how do cultural adaptations influence genetic evolution, and vice versa, across different species and environments?

Sleeping in groups: society evolves

Group sleeping can impact when animals sleep, how long they sleep and how deeply they sleep. For example, bumblebees suppress sleep in the presence of offspring; olive baboons sleep less when their group size increases; groups of meerkats time their sleep according to “sleep traditions”; and co-sleeping mice can experience synchronized REM sleep. To fully understand both sleep and animal social structures, we need to pay more attention to the “social side” of sleep, animal behaviorists from Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and the University of Konstanz argue in an opinion paper published on September 5, 2024, in the Cell Press journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

Although many animals sleep in groups, most sleep studies are conducted under laboratory conditions that only consider one animal at a time. These laboratory sleep studies provide high-resolution information on sleep depth and phase, but they are unable to capture the environmental or social contexts in which sleep usually occurs.

Meerkats sleep 10 to 12 hours a day, and normally go to bed in the early evening. Group sleeping lets them share body heat. Meerkats have “sleep traditions,” where neighboring groups show differences in sleep timing that persist through generations despite a complete turnover in group membership.

To understand the interconnections between sleeping and sociality, the researchers say that we need to study groups of sleeping animals in the wild. Social sleep is a research frontier, they believe, that holds exciting potential for new insights into both sleep science and wild animals’ lives. They propose a new framework that leverages simultaneous monitoring of the sleep of members of social groups, combined with time-series and social network analyses, to investigate how the social environment shapes (and is shaped by) sleep.

To study sleep in the wild, the researchers recommend using technologies such as wearable or implantable accelerometers, which provide information on animal movements with video or direct observations of the animals’ behavior. Pairing this sleep data with measurements of the group’s social networks, such as dominance hierarchies and kinship relationships, could provide important ecological and evolutionary insights into the impact of sleep on the fitness and survival of both individuals and groups of animals.

It’s likely that key aspects of group behavior, including coordination, decision-making and cooperative potential, will be influenced by the sleep of its members. By collecting data on sleep and sociality and applying their proposed tools to analyze social sleep, the paper’s authors say they can begin unraveling the adaptive functions and evolutionary trade-offs of sleep that may not be revealed by studying individual animals alone.

I have hope that understanding our co-cultures and those of the more-than-humans will help us create climate solutions that ensure that all of us thrive.

Thriving together: Earth endures

The climate crisis affects not just us but all the living world: where we all choose to live and how all our societies interact and operate. I have hope that understanding interspecies co-cultures—ours and others—will help us create climate solutions that allow all of us to thrive.

Because, as author Alan Weisman writes in his 2007 book The World Without Us, “without us, Earth will abide and endure; without her, however, we could not even be.”

Here’s to finding your true places and natural habitats,

Candy