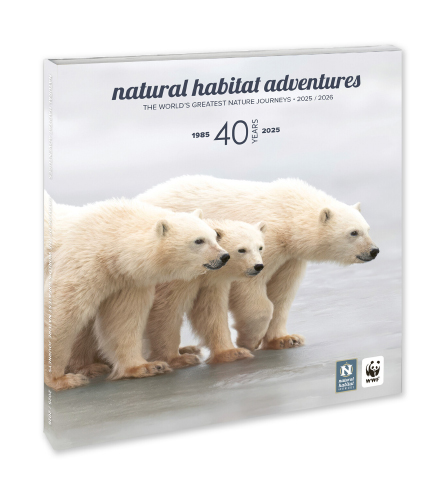

I traveled to Southern Africa on a Natural Habitat Adventures trip in October 2019, just a few months before COVID-19 crashed into our collective consciousness like a runaway freight train. In the two years that followed, amid the unending flow of grim news stories and the loneliness of lockdowns, I often returned to my memories of that place, finding solace in the simple beauty of a sunrise over the Okavango Delta or the sheer majesty of a leopard stalking her prey through the underbrush.

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

By the time I visited the African continent, I’d been employed as a writer for World Wildlife Fund (WWF) for three years. I love my job. As the largest conservation organization in the world, WWF has a presence in roughly 100 countries and our work touches a wide range of issues, from climate change to food waste and more. As a result, I get to write about topics that matter to me and perhaps even, in my own small way, have some positive impact on the world.

And yet, I must confess that, after three years on the job, I was starting to feel a bit removed from the problems we were tackling and the solutions we were championing. Each day, my work brought me to an office cubicle, not a research expedition in some remote locale where I could witness firsthand the fruits of our labor.

All that changed when I found myself on a two-week Nat Hab excursion to Botswana and Zimbabwe. I saw wonders there that heretofore had lived only in my imagination. A pride of lions dozing in the shade of an acacia tree. An adult rhino squaring off with his child in a playful, even tender, shoving match. A herd of wild buffalo at magic hour, trailing a sepia-toned dust cloud behind them. Zoo trips and photos are great, but they do not—cannot—fully capture the sense of awe that comes from seeing Earth’s most wild animals at home in Earth’s most wild places.

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

I also met people whose lives and livelihoods directly benefited from local conservation efforts. The rise of ecotourism in the region had transformed daily life in many communities. The income generated by wildlife guides, food service staff, and other local jobs, combined with revenue from local artists and artisans, paid for water pumps, roofs, and other essentials. For three years I’d written about how a thriving natural world contributes to thriving local communities, but those were just words. This was the reality behind our work, in all its splendor.

The time I spent in Southern Africa seems like a dream now, a collage of disjointed sights, sounds, and smells. But even though the memories may fade, they remain the gift that keeps on giving. That is what it means to be enriched by an experience. It stays with you. It changes you. It makes you a part of it. Forever.

I have often used terms like “natural treasure” or “ecological gem” in my writing when talking about the value of our planet’s rivers, oceans, grasslands, forests, and other critical ecosystems. And usually, when I write that, I’m talking about the trillions in dollars’ worth of benefits that these ecosystems provide to communities, nations, and the world-at-large. But these natural assets are a treasure in another way: they are the currency of a life worth living. They lift our spirits in times of trial. They are a reminder of all that has endured—and can continue to endure—if we can repair humanity’s broken relationship with the natural world.

Much of the world remains in the grip of COVID-19. I remain optimistic that this crisis too shall pass. But the larger crisis of our beleaguered planet persists. We can protect what remains, and even restore some of what has been lost, but we must rededicate ourselves to the task.

Humanity has the privilege of being the custodian of a rare and precious bounty. That’s a legacy we can all take pride in—and take part in. Starting right now.

By Jesse Marcus, WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF

© Jesse Marcus / WWF