Wolf or coyote? Would you be able to tell in the field? ©Henry H. Holdsworth

There’s an interesting, little book I picked up a few years ago. It’s titled Back in the Day: 101 Things Everyone Used to Know How to Do. Written by Michael Powell and published in 2006, the volume lists skills that used to be almost universally common—such as how to make your own butter or manufacture a barrel—but which are now almost absent among nonprofessionals.

While possessing those particular skills might be something we can all agree is no longer needed in today’s world, there are other proficiencies that have recently started to disappear that we probably would have a harder time deciding to deep-six: such as handwriting or understanding the meaning of nature words.

So, when I recently read a report out of the United Kingdom that stated that the ability to identify wildlife—along with being able to repair household items—topped a new list of endangered everyday skills, I wondered whether such know-how is just an inevitable victim of changing times or a loss we should strive to reverse.

Crow or raven? The best way to distinguish a crow from a raven is by looking at the appearance of its beak, wings and tail. Crows have a purple or green tint on blunt, splayed wings; while ravens have shiny feathers with blue or purple-tinted or grey and brown-tinted, pointed wings. Crows have fan-shaped tails and smaller, straighter beaks; whereas ravens have wedge-shaped tails with larger, curved beaks with a tuft of hair on top.

In other words, is the competence to correctly identify wildlife—without an app—still crucial?

The top 10 list of lost skills

According to Greeniversity, a nonprofit project in the United Kingdom that seeks to bring about a skill-sharing “revolution” among adults, repairing household items and clothes and being able to identify wildlife are the most threatened skills in the UK today. The organization’s Endangered Skills Register, launched during the 60th anniversary year of the queen’s coronation, highlights how expertise that was widely known six decades ago could be on the verge of being forgotten.

In the new study, Greeniversity researchers asked respondents which three skills they felt were most at risk from becoming a dying art. The two highest-ranking responses were chosen by almost half of the participants. The complete list is:

1. Repairing household items

2. Wildlife identification

3. Foraging for wild food

4. Making and mending clothes

5. Woodworking

Foraging for wild food ranked third on a list of skills that are becoming a dying art that was compiled by Greeniversity.

6.Traditional building techniques

7. Growing food

8. DIY and home improvement (hanging wallpaper, putting up a shelf, etc.)

9. Preparing meals from scratch

10. Fixing a bike puncture

A question of sustainability or progress?

In the years following World War II, stated Dr. Ian Tennant, Greeniversity’s development manager, families had no choice but to be resourceful. Gradually, however, it has become all too easy to move away from sustainable living. And, as history has shown, if these once-core skills are not passed on, they simply die out. Some believe that in these times of economic austerity, it’s vital that we preserve some of these skills for the next generation.

Just now, paging through that book of Powell’s, I see that listed in his 101 things that everyone used to know how to do are finding berries in the wild, growing herbs and making bread.

In the book “Back in the Day: 101 Things Everyone Used to Know How to Do,” finding berries in the wild is mentioned.

Perhaps that new list from Greeniversity isn’t so new, after all.

Do you think that being able to identify wildlife is a necessary skill in today’s world? Or are there now other means, such as apps, that are readily available and taking its place?

Here’s to finding your true places and natural habitats,

Candy

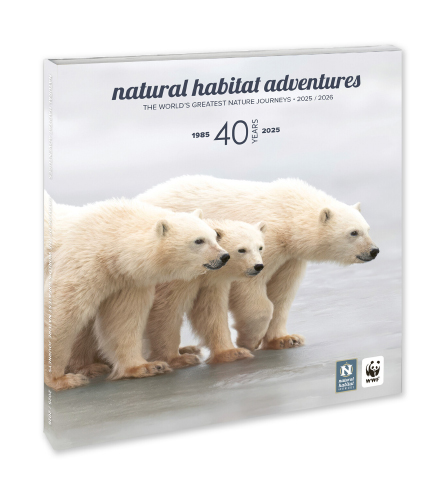

To help your children brush up on their wildlife identification skills, consider taking them on one of Natural Habitat Adventures’ family-focused trips, such as our Family Galapagos Adventure or Family Botswana Safari.

From my point of view it is important. At least in my study area, Plant Ecology, it is very useful to distinguish among species.

From a non-scientific point of view I think people like to know about nature and hence identify wildlife… or at least they ask me to tell them the names of plants. In any case giving names to things allow us to understand them and organize them in our brain so I don’t think it is an unnecessary skill.

I love teaching young people about the outdoors, from the macro to the micro. My favorite part is the “aw cool” moment! Technology is invading every aspect of our lives. When I am in the field, I am able to verify my identification of a species of fauna or flora by whipping out my smart phone and scrolling to an app. This is really convenient but its the knowledge of the genera and families that allows me to quickly seek out the suspected species. Without my background knowledge, I’d be aimlessly wandering through the app, not knowing what I was looking at. It is important for current and future generations to learn the basics of identification and understand how to use field guides to confirm identification, ESPECIALLY with the advent of apps like “LeafSnap” that claims to be able to correctly identify the species of tree from a picture the user takes of a leaf.

An essential skill and necessary knowledge Candice. Thank you for broaching this subject. In the UK, there are now no taxonomy courses. ! We have a volunteer culture. I am speaking as an entomologist. This is a very depressing situation. The UK does not value taxonomic expertise unless it helps industry or agriculture (the latter gets the funding). Ecology and biodiversity appear to be being side lined. I will find it interesting how many professionals in the field of taxonomy and museums, for example, will speak out. This is a political issue here in the UK. Experienced Museum staff are being replaced with volunteers, this has to stop.

It worries me that organisations such as the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff is loosing a significant number of senior staff from the Biodiversity Department, each with their own area of expertise, due to government cut backs, These are the very people that are needed to mentor and train the experts of the future.

For most of us, it’s not a necessary skill, or it wouldn’t be so rare. But that’s from an individual perspective, and a narrow one at that. It’s not necessary to be able to play an instrument, paint a picture, understand the major metaphors in a novel, grow plants, truly listen to other people, or cook. But these skills enrich one’s life and make it worth living.

For society, it’s better if people don’t settle for the minimum amount of learning it takes to get by. The less people know, the more likely they are to make idiotic blunders, and the more likely they are to fear those who know different things than they do. One person’s ability to understand another depends on being able to form analogies between what they already know and believe and what the other person does. An apt analogy makes the other person seem more familiar and less frightening. Natural history is loaded with apt analogies for understanding other people.

Also, people don’t care about things they know nothing about. The native plants in my area are like friendly faces to me: “Oh, wow! Indian cucumber! I haven’t seen you in forever!” To most people, Indian cucumber might as well be garlic mustard, so a dense invasion of the latter doesn’t trouble them. It’s a hot issue now, how much our ignorance and destruction of nature costs us, but I believe the costs are substantial. As a society, we need people to be familiar with the natural world so that they will value and preserve it. So, if it’s not priceless to them, at least it’s not worthless.

The ancient Greek botanist Isodorus said “If you don’t know the names, the knowledge of things is wasted”. He was a wise man. Without being able to identify an organism or plant, we can say little about it. All ecology is based on named organisms, which goes back to being able to identify them, there is little point gathering information about what an organism is doing until you know what it is. The level of identification is also important. All too often, I see important decisions on freshwater ecosystems being made on information based on family level identifications, which is problematic as different members within one family have a variety of ecological preferences. A much deeper knowledge is provided from species level identification, where one species may be tolerant to environmental changes, while its relative may be very sensitive. It is therefore very important to be able to accurately identify species. While this is not a skill needed by everyone, there must be a large enough group of professional people who have these skills for particular groups of organisms, to keep the skill alive in subsequent generations. Gene sequencing is a useful tool to help with identification and to help unravel relationships between species, but it will never replace the need to physically recognize taxa. So your botanist still needs to be able to identify plants properly, your invertebrate specialist needs to know the invertebrate group that he/she works on. This skill must never be lost, and it is encouraging to still see new identification guides being produced. I think that an interest in nature is something that should be taught to young children and nurtured, and with that interest comes the inquiring mind wanting to know what creature/plant they are looking at.

In order to sight-identify wildlife, one actually needs to see some wildlife, which involves (shudder!) going out of doors, something children and adults seem much less inclined to do these days than they once did. If a cell phone app can get people to look out their window at the birds, then perhaps venture out of doors for a closer look, lets cheer the cell phone app, and encourage more of them.

Loss of the ability to accurately identify animals in the broad sense (worms and snails, protozoans and bugs, not just furry and feathered critters) is also a dying skill. The techniques for identifying organisms, and formally describing the vast numbers not yet known to science, are not regularly taught to biologists in training at university level. It is argued that gene sequencing will be able to quickly and easily do these difficult tasks for us, but much current genetic research suffers from the objects of study having been misidentified. Even as concern increases to understand, catalog, and conserve the world’s biodiversity, the number of professionals and skilled amateurs capable of doing the basic work is in decline. Perhaps the future of primary biological research will be taken up by students in the developing world.

IDs can come from many sources…dichotomous keys are a useful technique, particularly distinguishing closely related taxa, and having value as learning technique by drawing attention to specific morphological characters. However, there are many excellent “trade” references with photographs and descriptions of common, and not so common, plants and vertebrates. Invert references lag behind, but this is changing too…example, a wonderful book by Univ Presses of Florida on Florida grasshoppers. There has also been volumes on rare and endangered species of Florida, FCREPA series, also published by Univ Presses of Florida. The internet is providing excellent sources for photos and info on plant and animal species, although you need to check the sources. There is no reason today for people not having access to accurate IDs and info on distribution, ecology, and vulnerable status.

There was an article in Science a decade or more ago that listed taxonomy as a critical skill in both plant and animal ID for conservation work. The history is interesting… In the 80’s when genetics were starting to become in vogue, the powers that be defunded almost all taxonomy programs in the country and gave it to the geneticists. I think there are only a hand full of programs in the US which gives advanced degrees and training in taxonomy. It has been a few years sich I had this conversation with a botanist friend of mine and she was able to name off the top of her head every school in the nation that had advanced studies in the subject. Speaking for myself, when I took botany it was in part to get an intro to keying. Unfortunately something happened during the course and the teacher had to cut something from the curriculum. Unfortunately it was training on the use of dichotomous keys…

I’ve read through the many responses of concern. Some with academic connotation from teachers / instructors, others from general outdoors enthusiasts, and some from biologists of varying fields of expertise. My response comes from all of the above but mostly as concerns pre-construction resource development surveys as relate to the potential impact on the local wildlife resource. Biologists considering themselves professionals cannot identify the species or its critical habitats are doing these surveys. The standards for credibility of those doing these surveys don’t exist, but the requirement for application approval needs to have this component “rubber stamped” as done; by anybody. Wildlife species habitat models are the surrogate to actually having to go into the field but the scale is inappropriate for identifying the key wildlife habitat features (e.g., nests, breeding wetlands, dens). Wildlife species sensitive to habitat disturbance and/or loss suffer for this lack of skill or effective attention to detail and thus become more threatened. Biodiversity databases are typically a recommended literature review to assess the possibility of sensitive species residing in an area, but if the proposed development area has never been surveyed before or if those lacking the appropriate skills to identify their presence then they often go overlooked. Regulators and professionals need to challenge the expertise of this skill.

Identifying regional wildlife and their signs is included as a core component of the Field Ecology course I teach. Additionally, it is standard fare for the non-profit organization for which I also work where we offer a program on it at least twice annually and invite the public to join us with wildlife surveys we conduct for a local nature preserve. Honing skill is a must for anyone conducting environmental education.

It is a necessary knowledge!

I feel there is a great necessity to make an encylopedia to list valuable native plant species of economic importance. ICAR, CSIR may try to undertake this job. I am not aware if already it has been done as I worked on crops.

A necessary knowledge! (needed)

Not necessarily, Ernie. The Google knowledge gained by, say a IT professional who may never go our in to the garden/park let alone a forest area would otherwise be lost.

Indian kids get a chance to go out on treks or at least watch slides and documentaries shot by wild life photographers and enthusiasts as par of their extra curricular activities. This reaches a very poor single digit percentage of society; the google experience has caused quite a few activists who are ‘motivated’ by what they read and see on the net.

There is a great need to strengthen this aspects at all levels of education through strengthening Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development methods. From my work experience of teaching students at the Giraffe Centre and whenever i take them on safaris to most of the protected areas in Kenya most of the time they cannot identify most of the species ranging from antelopes, cats, primates, pig family members among many others. Field trips for learners from different levels of education to nature areas should be encouraged.This trips should be more interactive and educative other than mere sight seeing trips. I have been using Interactive learning activities which use similar approach to the one mentioned by David Cook and it works to strengthen wildlife identification and ecological aspects!

Funny this just came up. I was asked to help my Niece to id some plants for a high school project. I told her if she wanted to get a good grade she should inform the instructor that he is doing these students a disservice by not introducing them to the Dichotomous key. I mean really this is the very basis of taxonomy and identification of organisms. I’ll talk to her about it again this weekend as I think if she introduces her class to the dichotomous key then that should earn her some extra credit. Just remember it is the dumbing down of the population that is the inherent enemy we must all fight. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZJoCfgAEuE

A very important step to caring and learning about the place one lives is to learn about the plants and animals native to their region. When we learn about the local flora and fauna then we will care for the natural environment in which they live. I think it is crucial and very important that we are able to identify wildlife in the place we live because we will be more likely to protect and care for it.

I think it is both a sign of the times and that we should be concerned. With people having to be constantly “plugged in” (especially the younger generation where a computer device is always at fingers length away) there is less of a need to go out and learn about something in nature. I am amazed at the number of people I interact with that are totally unaware of the natural world around them, to the point of not even being able to identify the plants in their own backyard…whether native OR ornamental! With this detachment from nature, more and more people are oblivious to the onslaught our environment faces from pesticides, pollution, urbanization, etc. I also find it funny that most of the people I see walking, running, or doing other types of outdoor exercising have an I-pod or other mp3 stuck in their ear. I take walks so I can hear the birds, hear the coyotes yipping in the evening, the nighthawks doing their aerial dive-bomb displays. I feel very odd and disconnected when I CAN’T hear, see, or smell what is going on outside when I am out there. Yet for most people, they need to be “connected” to some electronic device instead of connected to what is going on around them. As our society gets more and more electronic gadgets to do stuff for us and entertain us, I think we will continue to see a downward decline in the interest of most people with the natural world. I am constantly trying to teach my son about what is around him in the environment, little tidbits here and there about wildlife, insects, pollinators, habitat, etc. The other day I made sure he saw the Sharp-shinned Hawk that was in the backyard, perched on the fence and actively plucking and consuming a male House Finch. He says, “aw cool”, then, after a few seconds, went looking for his Nintendo DS. We should all take time to do this with our kids and hope that they at least grow up with some appreciation for the natural world around them.

My most treasured courses as an undergrad were those that taught me identification of native plants and animals. There was something about those classes that, as a student, really put the wheels to the pavement so to say- we immediately applied and practiced identification skills once we had a little bit of direction. I have to say that most people I know in my generation seem to lack any applicable identification skills- but then again that may have to do with the amount of time you have to invest to teach the students about identifying. I know that my department/university seems to be losing professors that are willing to teach the longer lab sections that address these skills.

I teach high school ecology. My thoughts on this are less scientific, however. The disconnect that my students are experiencing from nature and the world around them in general is disturbing. Knowing an animal’s identity on site is akin to knowing my students’ names. Without that identity, people cannot truly connect with that animal. The photo is that of a coyote, and I know that because I KNOW coyotes. I love coyotes because I know coyotes. It no more looks like a wolf than it looks like a fox, just as a person looks different from another primate. You can’t care about what you have no connection to….

I quite agree with Dick and others but if this is the case how is it possible that in the UK the university authorities and our Research Council seem ignorant of this and are not addressing this critical issue?

Necessary skill, we teach it at our house. And encourage learning it.

There was a study done a few years back (Suzuki, Bateman) in which 100 children from 4-9 (early development school age) were shown images or wildlife and corporate logos. I think it was something like 85% of the children could not recognize more than ½ of the animals while they got 100% of the corporate logos right. There was a follow up in which they looked at the children’s family lifestyle and school work. The children who could identify more animals came from families who regularly took walks in the woods, camped, rode bikes and generally played as a family. These children also scored higher in reasoning and problem solving and participated in class more. Not to mention they had fewer sick days.

This feeds the theory of Biophilia, the basic human need to be near or have contact with the natural world. I know in my case I always feel a lot better after a weekend of camping or even a long walk in the woods on a Sunday morning.

While we are at it, add common trees and plants to this list of things we no longer can call by their correct name!

We have The Wild Bird Count sponsored by the Audubon Society every year and I love counting the birds. It is a constant learning experience trying to study them and document which type, they have great charts to help you identify. Great way to get children involved too. Nature starts in your backyard.

What is (usually) the first step in making a friend? Learning their name. Stranger … name exchange … on the way to potential friendship.

I can’t tell you the thrill I felt, sitting on an intertidal beach making my little contribution to citizen science, when I could finally tell the sitka periwinkle from the checkered periwinkle. (With my students, I call this “making friends with the rest of Nature.”) That “deep seeing” was like the moment when we recognize a kindred spirit in a future friend. (I’m not sure the periwinkles were feeling the same elation, but that’s okay. I put them carefully back on their rocks.)

So I agree with Greeniversity that wildlife IDing and the resulting *connecting* is an important skill to bring back.

I think it is extremely important that field biologists know how to ID native plants and animals that live in our respective environments. This often requires help from experts that know specific taxonomic groups to help with these IDs. But also ee need to understand the distributions, habitat requirements, pollinators (in case of plants), and the ecological processes necessary for their maintenance. The same is true for exotic species so we can also understand what they are, their ecological needs, and their distributions, so we can respond to them in appropriate ways.

We should definitely be concerned. Learning about the natural world leads to a greater connection with it, which leads to a desire to conserve our planet. How can we hope that someone will care about an animal that they can’t even identify?

Relying on technology is definitely not the answer. Apps and books are useful tools, but owning them does not mean that you will be able to correctly identify anything. I work with many endangered species (bats, mussels, plants, etc.), and even experts sometimes have difficulty identifying some of them. Contrary to what various C.S.I. TV shows tell us, automated identification of many plants and animals is currently impossible. For example, training a person to identify the freshwater mussels of Kentucky or Tennessee is a process that takes years.

I realize that this article is mainly concerned with the wildlife literacy of the average person, but it is interesting to note that for many types of plants and animals there is currently a critical lack of taxonomists who can even identify the species.

Many people seem to have the notion that we have identified all of the plants and animals, and have turned that process over to machines. In truth, we are still finding and describing new species, and the basic life history of many plants and animals is still completely unknown.

As a naturalist, I find identification of wildlife useful “per se”, it gives me a lot of fun, really. But there is some applications that can be valuable for daily life. In our current world, we have cornered some species to tiny patches of suitable habitat, but many others thrive well amid human buildings, and we need to know if the uninvited creature that is eating our provisions, or just biting our wires, or interacting with us in other way, is e.g. a rat, a stone marten or a porcupine. Every day, in my work at a wildlife rehabilitation center, we receive a lot of answers about wildlife species found in urban environments, and animals caught within houses or garages. Identifying wildlife is a need, not a freaky hobby, even from an economical point of view, and it’s, for me, the funniest task to do.

Very vital as well as a crucial question? While inventorying biodiversity, we are facing problems in identifying lower group of wildlife and flora. There is a dire need to keep knowledge bank of taxonomist. This is such a skill which is not just acquired by academic degree rather a life long,laborious field work, practice and patience. thanks for raising this important subject.

There’s a massive trend, at least in South Africa, of people once again becoming interested in nature. It’s most obvious in the “nature” sections of bookshops, where the variety of field guides available, on everything from beetles to grasses to flowers and birds and trees and butterflies and geology is dazzling.

However, this may be more symptomatic of the loss of knowledge – people now need these field guides because they’ve forgotten, or don’t know, the names of things their grandparents used to know. And, of course, just because people buy the books with the best intentions doesn’t mean they use them.

There is also a trend of middle-class South Africans doing the “FGASA” (Field Guides Association of South Africa) training just for fun, with no intention at all of becoming a professional guide. These courses are intensive and a lot of hard work, and cost a lot of money.

So in general, I would say that (a) the ability to be able to name plants and birds and animals easily has disappeared but (b) there is a resurgence in interest in those skills.

Hello Candice, that you can google it tends to put those of us who are passionate about teaching it on the shelf! Learning the ‘old fashioned way’ is becoming obsolete unfortunately!

This lack of knowledge of flora and fauna is an indication of our overall loss of contact with nature and coincides unfortunately with a loss of appreciation for the natural world. As opposed to a century ago, a far greater proportion of people now live in urban settings and consequently know less about wild places and species. The less we know the less we care. As the process continues, we can expect voters to ignore conservation issues more and more. We only know the things we see, we only care about the things we know.

Fewer and fewer universities offer courses titled “Entomology”, “Ichthyology”, “Herpetology”, “Ornithology” or “Mammalogy” any longer because other more clinical and more “sophisticated” aspects of science have become priorities due to their marketability and potential for making money – which won’t matter at all if we have no natural ecosystems left to provide us with resources and vital services.

José (above) said, “To mankind, things that can’t be named are things that don’t exist.” I have a similar view. One of the first things we do on the way to becoming friends with someone new is to learn their name. So making friends with the rest of Nature means learning some names.

After decades of nature study / natural history in schools, for a while in the environmental education movement (70s and 80s), we said it wasn’t important to learn the names of other creatures — the “magic” of being outdoors was more important, we said. But I think it had more to do with how many teachers knew nothing about other species.

A few years ago, I was very blessed with the opportunity to visit South Africa. My husband and I decided to take full advantage of our trip and went on seven short safaris. I wrote down (and later recorded in my journal) the name of every animal we saw, or quickly sketched the ones we couldn’t name. We would ask the guide/driver for help, or check ID books back in our B&B. I think for others, the memory will be a blur of strange new four-legged creatures. But when I look over my diary of the trip and read of seeing a rock dassie or three kudus, I can picture them and where we saw them. It created a sort of relationship for me with them, and I’ll never forget them now.

Knowing the names of our neighbours of all species is important. (So is cooking a meal or fixing a flat bicycle tire.)

Thanks for this article Candice. Very important to pass on the skills to identify wildlife and to keep adding to our own knowledge of it. Keeps us in touch with the natural world, not just the virtual one. I have published some kids non-fiction books but having trouble finding a publisher for one on learning about what ornithologists do as the topic is too esoteric I am told. Sad!

I’m not sure up to what extend is this art dying as I was living in Panama and here lots of tourists come particularly for bird watching. But it is definitely very important we don’t let this type of Tourism disseminate, as promoting it would help teaching the value of wildlife and conservation. Probably schools could organize wildlife watching field trips.

It is a sign of the times, and we should be concerned. The loss of identification skills (all forms of wildlife, not just the animals) is symptomatic of our societal contraction to urban areas and also the loss of habitats and wild space. We no longer live in the wilds and too many of us fail to recognize the value of knowing and understanding what our fellow organisms contribute to the biosphere. There is also a greater move to pseudo knowledge, the apps and online knowledge that says to us, well, we can identify anything we want to without going to the trouble of learning.

Wildlife identification is a skill essential to any study of biodiversity. I was fortunate in being able to take courses requiring taxonomic ability throughout my college experience and became an entomologist in part because this field placed great emphasis on identification. As a professor I offered an entomology course in a small private liberal arts college throughout my career, perhaps gaining the distinction of doing so for the longest span at any U.S. institution of this kind during that period. It is unfortunate that such a course was and is not more widely available at liberal arts colleges in this country.

Sadly not news to those who work with identifiers and taxonomic keys. There are so many specialists that are approaching retirement age with no successors. This reminds me of an NPR story a while back https://www.npr.org/2013/06/19/184827651/animal-csi-inside-the-smithsonians-feather-forensics-lab

Few people are excited about spending long hours with a microscope and obscure terminology let alone a field guide. My blonde/white border collie has been identified as a wolf, coyote, fox and dingo by random adult passersby. Perhaps a sign of the times indeed, we no longer depend on knowing this information to survive.

Wildlife watching is a very rewarding pastime, encourages engagement and a sense of place, wellbeing and it is a valuable conservation tool for citizen science. An important factor of this is being able to correctly identify flora and fauna. My main career is in marine education but my love for the countryside came from my aunt and my Nan. As well as passing on identification skills they also passed on their passion for the countryside to me as a child (and added to my own passion for anything to do with the ocean).

I think that this passing on of knowledge and skills has greatly decreased and is a great loss. The current generation have access to technology which is a great resource but nothing beats being shown things first hand. I have been a biologist and environmental educator for 28 years, but put me in an unfamiliar habitat – such as grassland I will struggle. There will be some animals/plants that I will be familiar with from other habitats, some I can identify with the help of a guide but many others will be difficult to identify or separate from a similar species. So often put a specialist in an unfamiliar habitat and they become a novice.

I think on the plus side there are many organisations engaging the public and providing training course or similar opportunities. In fact I run some myself for different organisations locally. There is also an increasing number of citizen science projects such as Big Bird Watch and similar that can give people basic skills that are easier to then built upon themselves. There are schemes such as Ispot that allow people to identify their photographs on wildlife and also a variety of user friendly websites.

Even so, passing knowledge first hand – re identification is very important. There is also more to identifying an animal by physical features. I often see a more unusual bird visitor in my garden as a dark shape that moves differently to the birds I normally see or by a bird call. I have often spotted sparrow hawks and buzzards by noticing the behaviour change of smaller birds. In fact it was the change in the behaviour of herring gulls that led me to see my first red kite flying near my home.

In Sussex we have a great network of recorders feeding into the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre, I am one myself (for sea mammals). It is always necessary to verify a record before it becomes part of the data base and often, if the record does not come with a photograph, the observer has not noticed key features that will allow me to determine species – such as the difference in head shape between a grey seal and a common seal. Attending the annual seminar it is also very clear that a large number of these experts are already past retirement age and the concern I think is that the next generation does not have the same level of knowledge and skills to continue this valuable (and rewarding) work.

To mankind, things can’t be named are things don´t exist. It is a known fact in little children that only when they begin to name things, those things begin to exist in their brain. It´s true Judy, we should be very concerned if we want to conserve wildlife and nature

We should be concerned. If people don’t even know an animal exists and wouldn’t know what it was if they did see one, would they care if it went extinct?

It is sad to think that the majority of people today wouldn’t be able to identify most garden birds, insects or common mammals that we see in urban environments. I also think it is sad that a lot of people are scared of them and think that most animals are dirty, carry disease and will harm them or their property. Many children in England today do not even walk to school, and are carried to and from places by their parents in the cars, missing out on seeing the natural world. How many children even have access to greenspace or even rural areas?

Species are the building blocks of habitats and unless we can identify them we cannot say whether habitats are improving or declining. In other words our underlying scientific understanding of changes to our world depends on our abilities to be able to identify species and to understand their requirements. Such knowledge is not acquired overnight. Sadly universities rarely teach these skills nowadays and governments in the UK have been closing down key research stations which supported such skills. The main funder the Natural Environment Research Council perhaps needs to reconsider its priorities.

As wildlife identifier I should day, this is rather a science than an art, but you are absolutely right. It is partly because traditional morphological (external character) identification is partly (but far not completely) substituted by faster DNA identification, which does not require many years of education. This new method of identification is not yet fully developed, but is rapidly gaining. With recent progress in biological knowledge, many species turned out to be complexes of several externally nearly identical (cryptic) species, and you have to have either a very fine knowledge about species structure or use DNA analysis to distinguish them.

Wildlife identifications at http://www.taxonomicum.com

Yes, we should totally be concerned. One of the great joys of my life was leading tours to the Amazon, Africa and the Galapagos Islands, a big part of which was helping folks identify wildlife. If we lose this skill, we lose a sense of the variety and beauty of nature.

An endangered skill, how else can you tell the difference between a mouse, a louse or a spouse?

Cheers

Dan

At mid-century plus 10 I am just learning to identify wildlife and frankly -along with learning to horseback ride – it is the most empowering thing I’ve embarked on. I feel honored and privileged to count myself among those who know (or beginning to know, in my case) their way around wildlife and nature. I wrote a bit about this new way of looking at the world in a recent blog at weathereyefocus.com Just goes to show you’re never too old.

Hi Candice

great article because it is so true. On the other hand I can’t do half the things the younger generation can, such as work my computer properly. Incidentally, great photo of that cat walking in the mist.